| |

[ excerpt ]

also by the author:

Others' Paradise

Severin's Journey

into the Dark

Videos of Blaugast read and

performed at

Cabaret Voltaire (in German)

|

|

blaugast

A Novel of Decline

by Paul Leppin

translated from the German by Cynthia Klima

afterword by Dierk O. Hoffmann

Are you interested in catastrophes?

Blaugast is a tale of ruin. A bored clerk, Klaudius Blaugast, pursues his desires down a path

spiraling into complete degradation. Homeless and destitute, having lost everything to the evil prostitute

Wanda, he seeks redemption in a Prague that has become sybaritic and uncaring — a city in which he

has become an outcast among the outcasts. Flashbacks to incidents in his past, hallucinatory revelations

of the meaning of events long forgotten, point to the seeds of his eventual downfall.

Leppin's final novel, which he never saw published (the typescript languished for decades after his death in the

archives in Prague), Blaugast is an indictment of the despotic and vulgar, an exploration of the sadistic

tendencies found among the "moral" and "respectable." Max Brod's depiction of Leppin as "a poet of eternal

disillusionment, at once a servant of the Devil and an adorer of the Madonna" nowhere rings more true than here.

This is not a book for the prudish. With Blaugast's moral decline, he basically becomes the entertainment for

the orgy crowd. The book is heavy on atmosphere while exploring the shadowy corners of Prague nightlife. |

— His Futile Preoccupations

|

A frighteningly unsentimental novel of human degradation with echoes of both Kafka and Dostoyevsky. Written in the

1930s (the author died in 1945), the novel anatomizes the humiliation and decline of Klaudius Blaugast in the seamy underside of Prague.

The story begins with the title character accidentally meeting Schobotzki, an old school acquaintance, in the streets of Prague.

Schobotzki, a charismatic but nasty piece of work (and later termed "the most corrupt, the most evil ... the Devil incarnate"), startles

Blaugast by inquiring about his interest in "the science of decay" and in "catastrophes." It turns out the decay he refers to is

primarily sexual, for Schobotzki introduces Blaugast to Wanda, a prostitute specializing in degradation and debasement—not that

Blaugast, a self-described "pilgrim in the mire," needs tutoring in these areas. We're introduced to memories from Blaugast's early

sexual education, out of which he comes to the staggering revelation that "guilt, guilt, guilt was life, guilt that rose up, delirious,

in convulsions, to break down, tortured." Blaugast's journey borders on despair, for on some level he's looking for God and love,

both of whom seem to have deserted him in his "depravity and wickedness." Blaugast's abasement eventually becomes an obsession,

so much so that to the disgust of Wanda he quits his job and thus deprives her of one reason for her leechlike attachment. Johanna,

a girl from Wanda's "stable" (and with a proverbial heart of gold), steps into the breech, a Sonja figure who, in taking care of

Blaugast, finds herself "slowly submerged into a realm far removed from the mundane-a realm she had hungered for her entire life."

It is a spiritualrather than a carnal union with Blaugast. While Leppin's style is not as spare as Kafka's, the nightmare he chronicles

reminds us of our own connection to what Leppin calls the "Ur-forest," the dark realm of our repressed selves. |

— Kirkus Reviews

|

The King of Bohemia. |

— Else Lasker-Schuler

|

In a city where you can hardly walk a block before passing a statue or plaque

dedicated to a writer or artist, Leppin offers a stark contrast to many of his contemporaries, especially

Franz Kafka, who has been all but canonized by city officials in the past decade. Perhaps Leppin's Prague,

a world of tainted prostitutes, rotgut wine and syphilis, is less marketable to tourists than Kafka's

depictions of Austro-Hungarian bureaucracy. But maybe Leppin would have preferred it this way.

|

— Stephan Delbos, The Prague Post

|

With its disturbing descriptions of syphilis, prostitution, squalor, and

sadism, Blaugast may be compared to the work of the contemporaneous Neue Sachlichkeit

[New Objectivity] artists, particularly the Verists, so-called because their exaggerated satirical

naturalism forced the viewer to confront the harsh economic and political reality of the Weimar

Republic through the twenties and until its fall to the Nazis in 1933. Artists such as George Grosz,

Otto Dix, and Christian Schad combined aspects of prewar decadence and expressionism with harsh

realism in their depictions of mutilated war victims and syphilitic prostitutes. Similarly, though

with greater compassion, Leppin traces the deterioration of his protagonist, Klaudius Blaugast, from

a debauchee to a paralyzed, deranged syphilitic. Blaugast's increasing debilitation may be read as a

metaphor for the decline of Europe in the wake of World War I and during the years of the Nazis'

consolidation of power, which eventually culminated in a second world war. ... This translation is a

tremendous breakthrough for the study of German and central European literature. ... Blaugast paints

an unforgettable picture of the horrors of syphilis in a story that combines sin with saintliness,

debauchery with repentance, and degradation with forgiveness. |

— Kirsten Lodge, Slavic and East European Journal

|

In these pages we find the ultimate, amorphous horror of mere existence depicted in the most

graphic way ... It is certainly the case that all our beliefs — those cherished convictions on which we base

our view of 'the world' — are mere chimeras. Our faiths and our viewpoints are never accurate depictions of

reality. On the contrary they are merely a mode of obfuscation, they are a fragile form of insulation against the

traumatic dislocations and 'unspeakable' impossibilities of actual existence, against the sur-reality of the Real.

Because of his pre-existing disposition, because of his proclivities and because of the diabolical machinations of

Schobotzki, Blaugast is propelled into a vortex of disintegration — the disintegration of those too-fragile

psychic barriers that insulate him (and us) from the unbearable anxiety and suicidal despair arising from the

'distortions' of Reality. |

— Stride Magazine

|

The whole geography of the novel is filthy. The picture of Prague created by

Leppin is a city in moral crisis. The only glimmer of 'hope' (if I can call it that) is

Johanna, a prostitute whose own mother died of syphilis — will she 'rescue' Blaugast

from the hell he's descended into? |

— Annie Clarkson, Bookmunch

|

Paul Leppin's dark novels should not be read in spring, when the days are long

and full of bloom. His perfect, twisted little book Severin's Journey into the Dark and the

doubly twisted Blaugast: A Novel of Decline are meant to be read by candlelight in the deepest

nights of winter. Or perhaps one should approach Leppin's dark work beneath the watchful eye

of the sun, both for the sake of one's sanity and because Leppin is the sun's dark cousin. Where the sun

brings light to the world, Leppin revels in exploring the strange light that exists in the depths of

his characters' depraved souls. |

— Greg Bachar, Rain Taxi Review of Books

|

Blaugast is, in effect, the clearest expression of Leppin's archetypal

character: a man who abandons his staid, predictable life to throw himself into dreams, into the

expectation of sensual or emotional fufillment, especially in the anticipated apotheosis of erotic

love. It is only within these dreams that spaces tend to open up, colors become vivid, textures soften

... Leppin's final novel, as all of his work, is both a chronicle and a warning, a piece of decadent

literary history and a relevant standard through which to judge one's own progress or descent. |

— Karl Korner, The Prague Revue

|

Blaugast's astonishingly violent decline, from bourgeois life into the most

savagely depicted human degradation I can remember encountering in fiction, is so couched that

everything he experiences must be understood literally: even Prague itself. Here is the rag and

bone shop of true urban fantasy. |

— John Clute, Interzone, #213

|

A brilliant little novel. |

— Brendan Connell (author of The Translation of Father Torturo)

|

Even by the standards of a movement that glorified decadence, [Leppin's]

fiction is excessive. Swarming with prostitutes, anarchists, extortionists, infanticides, child

molesters, and exhibitionists, it delves into the deepest layers of depravity and moral and sexual

humiliation. |

— Tess Lewis, Bookforum

|

A more sensual writer than Kafka, more observant and horrifying than Brod,

more strange and free-spirited than Kisch, Leppin was a true son of [Prague].

Familiar with the whorehouses and bars, the machinations of shoemakers

just-getting-by and the pervasive decay of the Habsburg monarchy, Leppin guides his

readers into an underworld that's right around the corner. |

— Joshua Cohen, The Prague Pill

|

|

|

|

|

ISBN 9788088628071

2nd. edition

175 pp., 135 x 195 mm

softcover with flaps

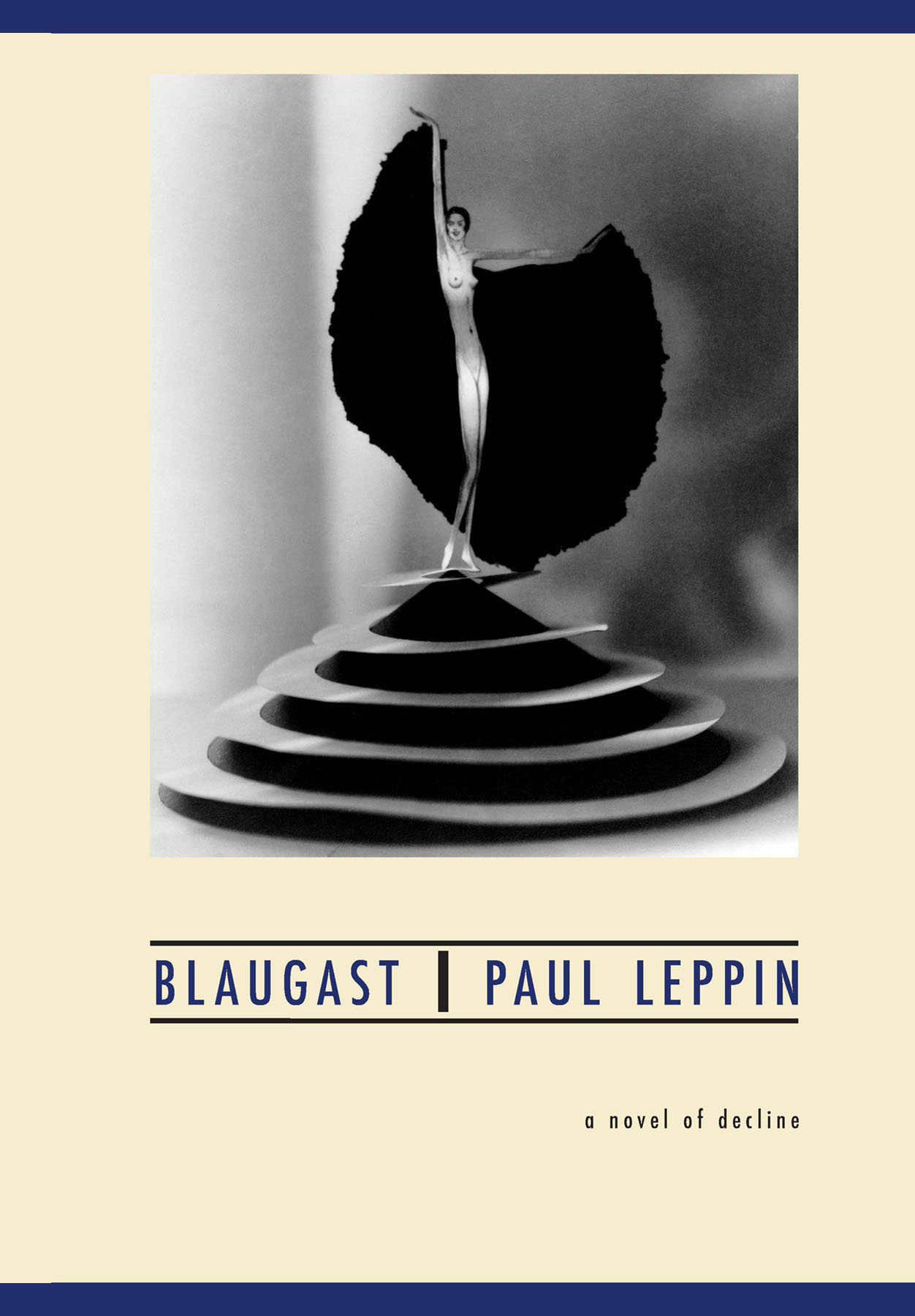

B/W frontispiece illustration

fiction • novel

publication:

1st edition: 2007

2nd edition: 2024

Order directly through PayPal

price includes airmail worldwide

also available from:

Wordery

Bookshops

Bookshop.org

Amazon US

Amazon UK

Central Books

e-book [978-80-86264-77-6]

Amazon US

Amazon UK

Amazon Canada

Amazon Australia

Amazon India

Amazon Germany

Amazon Japan

iTunes Bookstore

Kobo

|